The Risk We Quietly Accept: When Identifying Risk Is Mistaken for Managing It

A recent and widely reported street lighting column collapse, which resulted in life-changing injuries to a member of the public, has prompted a familiar response across the highway lighting sector. Predictably, attention has focused on ageing assets, corrosion at the base, inspection regimes, and whether existing guidance was followed closely enough.

Those discussions are necessary. They are also well rehearsed.

This is not another article that re-lists inspection failures or restates what guidance already tells us. Instead, it takes a step back and asks a more uncomfortable question. Not how the asset failed, but how the industry justifies the continued presence of known risk in the first place.

What the incident exposes is not a lack of knowledge, nor a lack of guidance, but a quiet acceptance of risk that has become normalised over time. It is this behavioural and decision-making aspect, rather than the technical cause of failure, that deserves closer examination.

Guidance Identifies Risk, It Does Not Control It

Industry guidance, including Institution of Lighting Professionals, GN22, is often treated as the backbone of structural asset management. In reality, its role is more limited and should be viewed honestly. GN22 is a framework for identifying and describing risk across large stocks of assets. It helps organisations understand condition, deterioration, and relative priority. It does not inspect columns, it does not test them, and it does not make them safe.

One of the difficulties that arises in practice is the way ALARP is applied at a portfolio level. Highway lighting is sometimes treated as a single asset class that can be balanced statistically. In engineering and legal terms, that is a fragile position, where each lighting column is its own electrical system, installed in public space, with its own failure modes and its own potential consequences.

A member of the public is not exposed to an average level of risk across a lighting stock. They are exposed to the column directly next to them.

When Inspection Stops Being Enough

Inspection should be exactly that. If an asset remains in the same condition as when it ‘left the factory’, structurally sound and free from deterioration, inspection alone may be sufficient. There is no justification for intrusive testing where there is no uncertainty.

However, the moment an asset shows signs of wear, corrosion, impact damage, or age-related degradation, inspection on its own ceases to be adequate. At that point, the asset is no longer known to be safe, it is merely assumed to be.

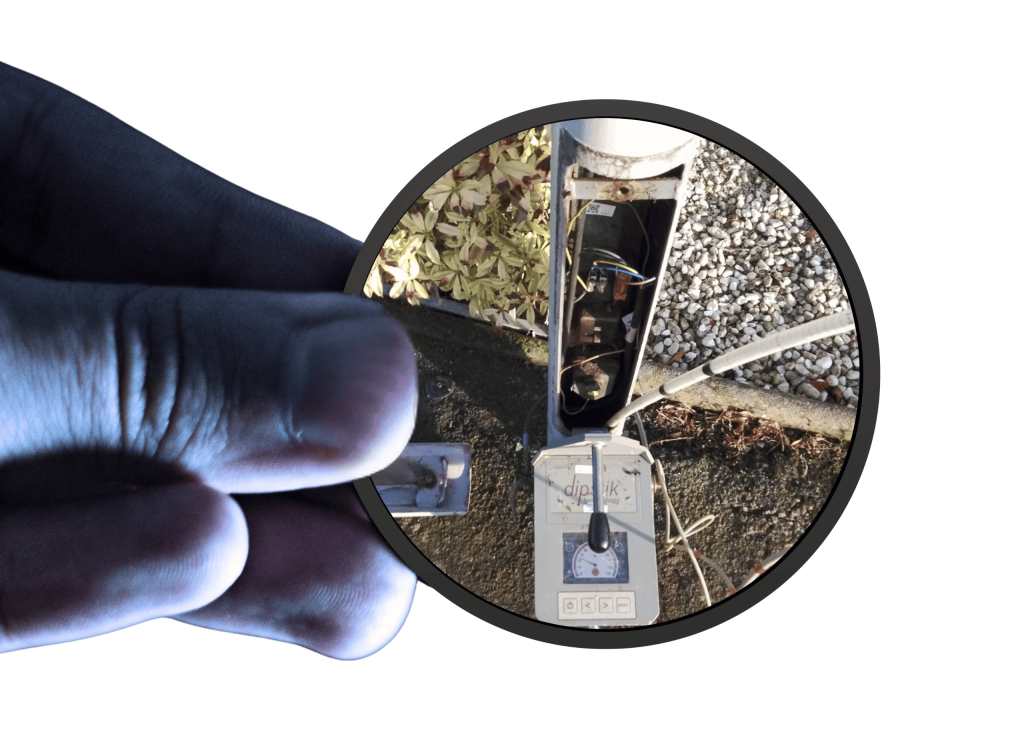

That uncertainty cannot be resolved by categorisation, modelling, or programme planning. It requires testing. Cyclical structural testing is not an enhancement in those circumstances. It is the only credible way of establishing whether the asset remains fit for purpose.

Probability Has Limits

One of the quiet assumptions that underpins many long-term asset strategies is that catastrophic failure is rare enough to be tolerated. Most columns do not fail. Many remain standing for decades beyond their design life. Over time, that experience builds confidence that the balance between risk and resource is reasonable.

Health and safety law takes a very different view once serious harm has occurred.

When a member of the public is seriously injured, the legal focus narrows sharply. It is no longer concerned with how many similar assets remained standing without incident or how low the statistical likelihood of failure appeared to be. The questions become simple and unavoidable. Was the risk foreseeable. Was the potential consequence severe. Were reasonably practicable steps available to prevent harm.

If the answer to those questions is yes, it becomes extremely difficult to argue that the duty of care has not been breached. The occurrence of the accident itself is powerful evidence that the risk was not adequately controlled.

At that point, probability loses its protective power. Statistical comfort, while useful for asset planning and prioritisation, carries little weight once exposure has resulted in injury. A single failure is enough to trigger scrutiny, because health and safety law is concerned with harm to individuals, not success across a population of assets.

This is not a conflict between guidance and law. It is the point at which guidance has done its job and the law steps in to judge what was done with the knowledge it helped to identify.

A More Grounded Approach

Large-scale asset management frameworks have their place, but they can also create distance between decision-makers and individual assets. That distance makes it easier to defer action and to tolerate deterioration for longer than is defensible.

A more robust approach is simpler and more aligned with both engineering reality and legal duty. Inspect assets honestly. Where deterioration is present, test them. Where uncertainty remains, remove exposure. Treat each column as the individual system that it is, not as a data point within a statistical model.

Closing Thought

The Health and Safety at Work Act is deliberately principle-based. It cuts through complexity when harm occurs. In this case, the breach of Section 3(1) and the resulting fine were not about paperwork or process. They were about exposure to a foreseeable risk that was not adequately controlled.

Guidance has a role, but it should never be mistaken for a safety control. Identifying risk is not the same as managing it, and managing portfolios is not the same as protecting people.

When wear and deterioration appear, certainty must come from testing and timely action, not from comfort in numbers. Because when something goes wrong, the law does not ask how well the risk was modelled. It asks whether enough was done to keep people safe.