Across the UK, structural safety of lighting columns is a matter of public trust, engineering integrity, and increasingly, legal and financial liability. Yet, while most local authorities appreciate the importance of inspecting their street lighting stock, many still rely on non-accredited providers or procurement processes that prioritise cost over competence.

It’s time for a sector-wide conversation about why accreditation should be the national minimum standard for structural inspections of lighting columns.

Local authorities are not legally obligated to provide street lighting. However, once installed, they are responsible for ensuring that such infrastructure does not pose a risk to the public under the Health and Safety at Work etc. Act 1974. A lighting column that collapses due to undetected structural failure moves a council’s responsibility from passive nonfeasance to active misfeasance, potentially incurring serious civil or even criminal liability. Past cases, such as the Westminster City Council prosecution in 1998, are a sobering reminder of the legal consequences of inadequate inspection regimes.

The Role of National Accreditation

UKAS (United Kingdom Accreditation Service) accreditation to ISO/IEC 17020 or 17025 demonstrates that an inspection body is competent, impartial, and operates to international standards. It’s a rigorous process involving quality audits, staff qualifications, and procedural validation—offering a public assurance of trust and capability.

This standard provides a consistent benchmark across the UK—so that a structural inspection carried out in England, Wales, Scotland or Northern Ireland adheres to the same level of rigour and impartiality. While specific methods may vary by provider or region, the expected quality and safety assurance remains consistent.

To put this in perspective, in a wide range of safety-critical industries, insurers and regulators already insist on accredited providers—often under ISO/IEC 17020 for inspection activities. For example, fire alarm and intruder alarm systems must be installed and maintained by companies accredited under UKAS-approved schemes (such as NSI or SSAIB) to comply with insurance requirements. In the lift industry, safety inspections must be undertaken by UKAS-accredited inspection bodies in accordance with the Lifting Operations and Lifting Equipment Regulations (LOLER). Pressure systems, such as boilers and autoclaves, require periodic inspections carried out by UKAS-accredited bodies under the Pressure Systems Safety Regulations (PSSR). Gas safety inspections in commercial environments similarly rely on accredited inspection regimes to satisfy both legal and insurer expectations. Even in fields like asbestos surveying and legionella risk assessment, ISO 17020 or 17025 accreditation is routinely used as a benchmark of impartiality and technical competency.

This is not seen as a burden—it is rightly viewed as the bare minimum to ensure safety, reliability, and legal defensibility. Why should the structural testing of lighting columns, which if failed can cause catastrophic harm, be held to a lesser standard?

Why should the structural testing of lighting columns, which if failed can cause catastrophic harm, be held to a lesser standard?

The Illusion of Competence

The industry must also challenge the fallacy that hiring equipment equates to being qualified. Just as hiring a mini digger does not make one a qualified plant operator, or hiring a multifunction tester does not make one a competent electrician, hiring a structural test device does not confer the knowledge, experience or accountability needed to perform safety-critical inspections.

Competence in this context demands more than familiarity with a device—it requires an auditable system of training, assessment, method validation, data analysis, and quality assurance. Accreditation provides a framework within which all of these elements are independently verified. It is not possible to duplicate that standard with ad-hoc hire and a self-declared methodology.

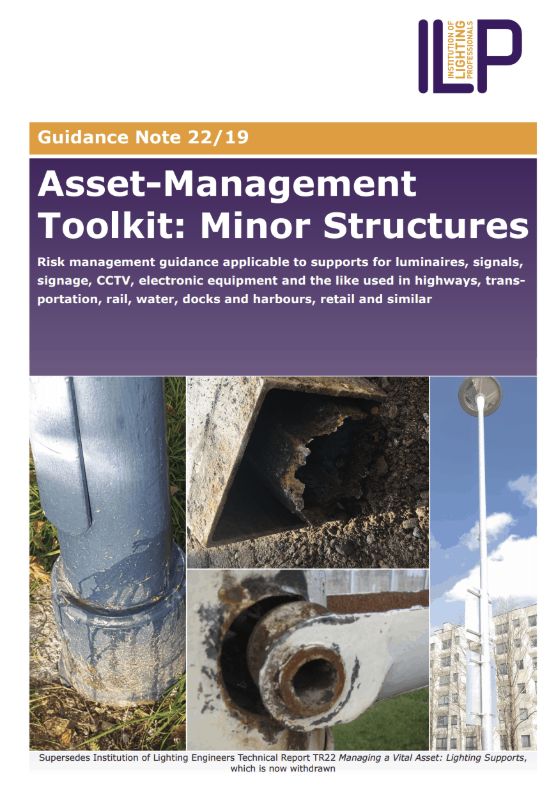

This distinction was clearly demonstrated in the Westminster case. The issue was not the absence of a testing regime, but that the regime in place failed to detect severe internal corrosion—failures which could have been avoided by applying more advanced or recognised inspection methods. This illustrates that simply having a process is not sufficient; that process must be robust, fit-for-purpose, and carried out by a demonstrably competent party. Accreditation provides the assurance that these conditions are being met.

There are existing schemes within the highway electrical sector that support general workforce competence and training standards. However, these schemes are not specialist accreditations for structural inspection. While they play a valuable role in maintaining baseline industry competency, they do not typically encompass the specific procedural, technical, and quality requirements involved in structural testing. Accreditation fills this gap by ensuring a higher level of scrutiny and assurance tailored specifically to inspection activities.

Insurance and Liability Implications

Beyond the core duties outlined in the Health and Safety at Work etc. Act 1974, the Management of Health and Safety at Work Regulations 1999 also have clear relevance. Regulation 3 places a legal requirement on duty holders to carry out a ‘suitable and sufficient’ assessment of risks to employees and others affected by their undertaking.

This duty is upstream in nature: it is not merely about producing paperwork, but about taking forward actions that reflect the findings of those assessments. Where structural failure of street lighting columns is a foreseeable risk, and where more robust, accredited inspection methods exist and are widely recognised, relying on a non-accredited provider could reasonably be considered insufficient. In this context, competence is not a matter of convenience—it is a legal standard that influences both prevention and liability.

The following case is often referenced as a pivotal moment in understanding local authority liability for lighting infrastructure failures:

Westminster City Council were prosecuted under Section 3 of the Health and Safety at Work etc. Act 1974 after a corroded lamp column collapsed in Cavendish Square, seriously injuring a pedestrian. The council was fined £8,000 plus costs. In addition to the criminal prosecution, civil proceedings led to a reported settlement of over £3 million in damages, alongside an annual payment of approximately £110,000 to the injured party for the remainder of their life.

Crucially, the prosecution highlighted not that there was no testing regime in place, but that the regime used was inadequate, failing to identify internal corrosion that better methods available at the time would likely have detected. This underlines a vital distinction: having a system is not enough—it must be the right system, delivered competently. This incident has been cited in professional guidance, including ILP member briefings and GN22, as a lesson in the importance of rigorous inspection standards and independent competence validation.

The insurance industry increasingly expects public bodies to demonstrate that they have taken all reasonable precautions to mitigate risk. If a street lighting column collapses and injures a member of the public, an authority must show that it used a competent inspection provider. If the provider is not UKAS accredited, the council may face difficult questions: Why was an unaccredited contractor used? How was competence assured? Were procedures in place to verify that inspections met the latest standards?

In some cases, a lack of accreditation could be viewed as a failure to take reasonable precautions, which might jeopardise the validity of an insurance claim or open the door to regulatory enforcement. In contrast, using a UKAS-accredited provider strengthens a council’s legal defence, evidences due diligence, and provides insurers with assurance that risk has been properly managed.

Case law reinforces this position. In R v Westminster City Council (1999), the council was prosecuted under the Health and Safety at Work etc. Act 1974 after a corroded lamp column collapsed and seriously injured a pedestrian. The court found that the council had failed in its duty of care despite having an inspection regime in place, because the methods employed were inadequate to detect internal corrosion. This case underlines the importance of not only having a regime in place, but ensuring that it is competent, fit-for-purpose, and demonstrable—qualities inherently supported by UKAS-accredited systems.

A Call for Consistency and Leadership

We must ask ourselves—why is UKAS accreditation the norm in comparable safety-critical inspection sectors, yet optional in ours? The argument that accreditation reduces market choice or increases cost is rapidly being outweighed by the rising risks of liability, reputational damage, and public safety.

Accreditation should not be viewed as red tape or over-engineering. Like regular MOTs for vehicles or EICRs for buildings, it is a structured, evidence-based way to ensure assets do not quietly become liabilities.

As professionals committed to quality, safety, and public service, we should not wait for another incident to drive change. The ILP and its members have an opportunity to lead by example, advocate for clearer national guidance, and support clients in updating procurement policies. UKAS-accredited structural inspections should no longer be seen as a gold standard—they should be seen as the basic standard.

One practical step would be for authorities to begin auditing their current inspection providers and to include UKAS accreditation as a preferential criterion in future procurement. This does not preclude competent providers, but it does signal an upward shift in expectations, aligning the sector with other risk-managed fields.

To support this, professional bodies and the ILP could issue joint guidance notes or model clauses for local authority use, helping procurement teams frame specifications that prioritise competence and assurance. Presentations, regional workshops, and panel discussions at industry events would provide further opportunities to build consensus, share case studies, and offer practical steps for implementation.

The structural integrity of street lighting columns is not merely a technical issue—it is a public safety responsibility. Accreditation is not a luxury; it is a necessity. By promoting UKAS accreditation as the minimum requirement for structural inspections, the lighting profession can take a proactive, evidence-led approach to managing risk and improving standards.

We owe it to our clients, our communities, and ourselves to raise the bar.